|

|

|

|

Questions to Get Your Book Club Talking

1. Why do you think the author chose to tell the story through the points of view of Hope, one of the Wednesday Daughters, and the pages of her mother’s journal? What element does Ally’s journal entries add to the reading experience?

2. What is the importance of Beatrix Potter and her children’s stories? Are there any books from your childhood that remain important to you, as Beatrix Potter’s tales remained to Hope?

3. How does Hope and Kevin’s relationship change over the course of the novel?

4. The topic of race and feeling like you are “two different halves of one thing” (page 186) is salient throughout the novel. How do the characters deal with this?

5. Early on we see the close relationship between Anna Page and Ally, which is even closer than that of Anna Page and her own mother. What do you think it was like for the Wednesday Daughters to grow up with multiple mother figures? How is its impact on their development shown in the novel?

6. What did you think of the relationship between Julia and Isaac? Do you think it was love or shared grief? Why?

7. How much do societal expectations influence the characters in the book? When do the characters use these expectations as a restraint? When do they use them as a way to become stronger?

8. Ally and Beatrix reflect on Graham’s point that “the fact of another’s suffering doesn’t lessen our own.” (page 249) How do the characters come to understand this?

9. As a doctor, Anna Page takes care of people for a living, yet she refuses to let anyone take care of her. Why do you think this is? Does she change?

10. The characters spend much of the novel trying to find a sense of belonging. Do you think they achieve this goal? Who in particular does or does not? Why?

11. Do you agree with Anna Page’s maxim “A heart at rest is death”?

12. Ally and Hope both spend their time at Ainsley’s End searching for a deeper understanding of their familys’ past. Why are the characters fixated on discovering this truth? What type of knowledge do we hope to find when investigating our family’s history?

13. Robbie wonders, “How’s a person to be interesting without her scars?” (page 147) What scars do the characters have? What do our scars say about us?

14. Of all the themes in the novel—race, secrecy, family relationships, forbidden love, growing up, etc.—which resonated the strongest with you? Why?

An Interview with Meg

Caroline Leavitt is the New York Times bestselling author of Is This Tomorrow, Pictures of You, and eight other novels. She can be reached at www.carolineleavitt.com.

Caroline Leavitt: Meg, you and I have been friends for quite a while—since 2002, I think. We met on Readerville, but we didn’t meet in person until 2011, at the Gaithersburg Book Festival. Which is fitting because so much of your new novel, The Wednesday Daughters, is really about friendship. Sometimes I think that our deepest friends really become our family, often because we can’t reach our family with enough depth to also make them our friends. Would you agree with this?

Meg Waite Clayton: It’s so hard to move aside the cobwebs of our childhoods, isn’t it? I’m only fifty-five, though, so perhaps there’s still hope! I suppose my parents and perhaps even my brothers know me better than I like to think, but the people I can really talk to are my closest friends. And it’s a lovely place of safety from which to write, friendship. I’m pretty sure my friend Jenn, for example—having put up with me as a roommate for three years of law school and stayed with me through all sorts of unpleasantness over three decades now—is with me for life, as I am with her. I imagine she’s chosen to love me even with my faults, or because of them. That’s certainly how I feel about her.

We don’t have much choice about our families, but the love we feel for friends, that’s a love we choose every day, and the love is all the stronger for the choice.

CL: What made you return to the daughters of the Wednesday Sisters? Did anything surprise you in the writing?

MWC: I didn’t actually mean to write a sequel. I wrapped up The Wednesday Sisters with an epilogue, and thought I was done with their stories. Then I was talking with someone about his children, who are biracial, and it dawned on me that Ally’s daughter, Hope, would likely have faced the kinds of identity issues many children of mixed race do. I thought those issues would be really interesting to explore in themselves and as a metaphor for the sense of non-belonging that so many of us experience. And readers had been asking if I would do a sequel, so one that involved the daughters of the original five friends seemed somehow meant to be.

Two things that surprised me in the writing were the role Peter Rabbit author Beatrix Potter ended up playing in the novel, and the fact that Kath—the character in The Wednesday Sisters with the misbehaving husband—would not bend to my will in this book, either. I appear to be no better at making her behave than she is at making her husband do so! It turned out to be such a warm pleasure to revisit these old friends—and to see them through the eyes of their grown daughters—that I find myself wondering if there might be another Wednesday book of some sort, someday.

CL: There’s something so mesmerizing about the relationship of mothers and daughters—what we think we know versus what we need to find out. As Hope and the other Wednesday Daughters go through Hope’s recently deceased mother’s letters, they don’t just confront her life, they confront their own. What do you think makes our mother-daughter bonds so important? Do you think we need to find a new way to navigate those relationships?

MWC: It’s impossible for a parent not to have dreams for her children, and impossible or nearly so for a child to fully let go of the need to please her mother. It’s particularly complicated, I think, for women of my generation, who grew up with 1950s-era mothers and are now trying to negotiate the twenty-first century. Some of us have chosen paths our mothers abhor. Some of us feel pressure to live the lives our mothers couldn’t. The expectations for our two generations are so different despite the very few years that separate us.

It seems life would be so much easier if we could talk freely with our parents, and yet that’s so much more difficult than it seems it should be. I try to bring out this contrast in Hope’s and Anna Page’s interactions with their moms. Anna Page turns to Hope’s mom, and Hope turns to Anna Page’s, but neither is that good at talking honestly with her own mother. The burden of expectation is hard to set aside.

And yet, at some point, we have to let go of our parents’ expectations for us. And when it’s our turn, we have to let our children loose to make their own mistakes. And that bit—letting your children make mistakes—is really tough.

CL: What I loved so much about both The Wednesday Sisters and The Wednesday Daughters is that you look at the mother-daughter bond from the viewpoint of each. Did being a mother, as well as a daughter, color what you wrote? (I know being a mother certainly has changed the way I look at my own mother-daughter relationship.)

MWC: I only have sons, but I have to say that being a parent has completely changed my view of my mom. Who knew when we were growing up how hard what she did for us was? The Wednesday Sisters was certainly meant as an homage of sorts to my mom and her friends. It gave me an excuse to talk to her and explore what her life was like. Trying to put myself in her skin really changed my view of her—for the better. And I do carry her mothering and my own into everything I write. I even lift some moments from my journals, and then fictionalize them. Quite a bit of what children do in my novels has been done by my sons.

CL: So much of both these books is about writing—what it means to us, how it frees and sustains us. How much of what you think and feel about writing finds its way into your characters?

MWC: I think the best writing comes from exploring what we are passionate about, and I’m certainly passionate about writing. I’ve come to know myself so much better as a writer than I ever did before. I dip into that emotional space pretty regularly through my characters—I suppose in part to invite readers to try writing themselves. (Really, jump in, the water is fine!)

But like most writers, I came to writing first as a reader, and much of how I think and feel about writing has roots in my love of reading, and in the books that have made me who I am, or at least brought out whatever good there is in me. When I sit down to write, one little part of me is Scout Finch.

CL: What’s your writing life like? I’m always interested in process, maybe because part of me worries that I could be sharper or clearer, or that I’m somehow doing it wrong. What’s your process like? Do you map things out, fly by the seat of your pen, follow your muse?

MWC: My answer to pretty much all the “Do you” questions about writing is “Yes.” I start any way I can, often in my journal. Since no one but me reads them, the pressure is off, which I need when I’m starting a project. Often I just sit down and write a word—any word—and hope other words will feel sorry for it and come sit beside it, in the next empty space. Words are a bit like friends: if you open yourself up to the possibility of them, good things happen.

Once I spill ink, the words do come eventually. So the one rule I have for myself is to sit down and write every day, from 8:00 A.M. to 2:00 P.M., or 2,000 words when I’m writing a first draft. It’s a discipline I started when my children were young, based on their school schedule. I claimed that time for myself. I didn’t think about groceries or bills. I didn’t even answer the phone (although I did listen the answering machine, in case it was about the boys) until I either had 2,000 words or it was 2:00. If I had 2,000 words by 11:00 A.M., I could pack it up and eat bonbons and watch old movies or read good novels all day long (or go to the grocery store). But the fact is if I hit 2,000 words in the morning I wasn’t getting up from the chair because that was a clear sign the literary gods were smiling on me. Now that my sons are grown, I sometimes start earlier and take a break to read the paper with my husband when he wakes up, but I put in six hours a day. Once I’ve got the first draft, I can edit for days on end. At that stage, my husband is often prying me from my office chair to join the real world at dinnertime.

One of the tools I find very helpful for writing an ensemble novel is a character scrapbook. It is, quite literally, like a scrapbook from your childhood—a collection of all sorts of bits that help define each character. I often start with pictures I’ve torn from magazines—not one picture of a person, but rather one person’s eyes and another person’s nose and another’s physique and another’s wardrobe choices, all put together on the page. I set aside pages for settings, too. I include things nobody else needs to know—like what cars my characters drive or who their childhood boyfriends were—things that help me flesh out the characters in a way that makes them feel real to me. They need to feel real to me for me to make them feel real for the reader. I also add snatches of dialogue. And I continue adding to the pages of the scrapbook as I go along.

I also use outlines and flowcharts. One of the things I find useful about a flowchart set up by chapter and character is that I can see if, perhaps, I haven’t touched on a particular character’s story in four or five chapters. It’s a very helpful visual aid. Also, in my office, I surround myself with inspiring, thought-provoking pictures.

CL: What’s obsessing you now and why?

MWC: Chocolate. No, seriously. Chocolate. I’m thinking of using it in a big way in my next novel. My favorite thing to cook has always been brownies, and I once received a marriage proposal based on the fact that the suitor in question would get to eat my brownies until death did us part. Now I’ve got my eye on a class in making fancy chocolate candies.

CL: Can we talk about the cover? This one is particularly lovely, with the scrolled door. What kind of input did you have on the cover, and have there ever been covers you weren’t happy with?

MWC: I love this cover. I love it so much that I was reluctant to admit it for fear I would jinx it. When my editor asked if I had any ideas about what I wanted the cover to look like, I sent her a photo of my husband in front of the simple blue door of a stone cottage in which we’d stayed. Robbin Schiff, the art director at Random House, either ran with my idea of a blue door or came up with it independently from the blue door on Ally’s cottage in the novel—I’m not sure which. But the result is so evocative. The slightly ajar door is so enticing, and the envelope tucked into the ironwork . . . look closely at the addressee!

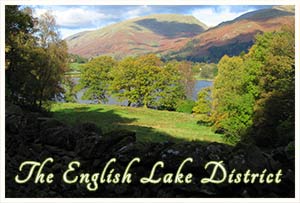

CL: The sense of place in the novel is so real that you can almost smell the lake air. In fact, the world you’ve created is very much a character in itself. How did you decide on your setting, and why?

MWC: The honest truth about why The Wednesday Daughters is set in the English Lakes is that I wanted to set it in Italy, but my editor at the time wasn’t enthusiastic about an Italian setting. She loved the idea of the story, but felt my American readers would prefer an American setting. So I looked at my bucket list of places I wanted to see and tried to find angles that would appeal to my editor.

I knew she was a Beatrix Potter fan, as am I, so I approached her with the idea of having a Beatrix Potter angle, then just happened to mention that Potter lived in the English Lakes. Her response was a joking “Well, England is sort of like a suburb of the United States!” And we settled together on setting the novel in part in the San Francisco Bay area and in part in the English Lakes.

I’d never been to the Lakes when I signed the contract, but I did immediately arrange a stay at a little cottage on Windermere.

The Lake District turns out to be among the world’s most magical places: waterfalls and lakes and mountain ponds, bracken-covered fells and green valleys, stone manor houses and cottages, friendly people, footpaths everywhere.

We stayed in Bath, England, on the way to the Lakes, in a bed-and-breakfast with a slipper tub at the foot of a lovely four-poster bed in the top-floor room—exquisitely romantic bubble baths! If you don’t find yourself madly in love with your traveling companion on a trip like that, you need to trade him in for someone else.

CL: Tell me more about what inspired you to add Beatrix Potter to the story. It’s completely charming how Ally writes about her time with Potter, even as the daughters, reading the entries, wonder if this is madness or a new kind of creativity. I’d love it if you could talk about how the author and her stories fit into your themes.

MWC: I am a huge fan of Potter’s “little books.” And I’d pitched the Beatrix Potter angle as a way to get to an English Lake District setting. So I sent Ally on a mission to write a Potter biography, and I thought that was going to be it—her doing research on Potter in the English Lakes.

The more I learned about Potter, though, the more enamored I became.

She was self-published: After a black-and-white version of The Tale of Peter Rabbit was rejected by every London publisher she sent it to, she had 250 copies published privately on December 16, 1901—which quickly sold out, as did the 200 more printed in February 1902. (The 8,000 first printing of the color version—with Peter’s blue jacket—sold out before its publication date in October 1902.)

Her early books began as picture letters to children of friends, which she later borrowed back. From age fourteen to age thirty, she kept a journal in a complicated code, 200,000 words (the length of two copies of The Wednesday Daughters and then some) that weren’t deciphered until years after her death.

She started writing to gain financial independence from her parents, and yet she opposed suffrage and, after she was married, lamented that people forever forgot to call her Mrs. Heelis.

The more I learned about Potter, the more I felt that the few facts I was dropping in as a part of Ally’s research didn’t do this delightful woman justice. The idea to bring her alive through Ally’s journals—as a traveling companion of sorts—came to me on a long, boring drive. I didn’t even tell my husband about it until I’d written a few of the journal entries and had a better idea that it might work. I had so much fun writing those journal entries. And the wisdom Potter offers on writing and on life—which I culled from her writings—was a terrific education for me.

CL: The Wednesday Daughters explores how we are creative, both on the page and in the way we shape our lives. Do you think it’s ever really possible to absolutely know the right thing to do at the time we need to do it? Do you also think it’s possible to know someone as completely as you know one of your characters? And would we want to? Or is there something to be said for the secrets we keep?

MWC: This is such an amazing question, Caroline. When Kath first walked away from scenes I had in mind for her in The Wednesday Sisters, I was sure I could bludgeon her into doing my will. But she wouldn’t be bludgeoned in that book or in Daughters, either. She comes up with these reasons for her choices that cause me to step back and say, Oh, I do understand that, as much as I hate it. I’m not sure I completely understand her, even though the only place she really exists is in my mind. And if I’m wrong about what’s best for a fictional character that is my own creation, I’m quite sure I’m as frequently wrong about the choices I would have my real life friends make, and the choices I make myself. Which is a long way of saying I don’t think we can ever really know the right thing to do, even in retrospect. But if we don’t make choices, we have no way to move forward.

I’m not sure I know even my own characters completely—which is perhaps an admission that I don’t know myself very completely, either. On some level, I suppose I recognize that my stories are a way of putting my own secrets out in the world without having to own them.

So perhaps that’s the beauty of being a fiction writer: you can unburden yourself of your secrets without having to admit to them. You stir them into a batter of emotions you bake into a novel, and as you hear from readers that your stories make them feel understood, you too feel understood.