I am working through plotting issues myself and returned to these notes from a master class I taught on narrative endings a couple years ago. They are just my notes, which may or may not be helpful to anyone who did not attend the lecture. With that caveat, I’m bumping them up for others to more easily find them (and to more easily find them myself!):

PADDLING YOUR BATHTUB INTO LONDON:

HOW GREAT STORIES END

“Writing a novel is like paddling from Boston to London in a bathtub. Sometimes the damn tub sinks. It’s a wonder most of them don’t.” – Stephen King

The 3 Rules for Ending any Narrative Work

Rule #1 Give the reader what they want, but not in the way they expect it. “SURPRISE”

Rule #2 Do it Slantwise, which means you have to start paving the Yellow Brick Road at the beginning. “INEVITABLE”

Rule #3 There is no Rule #3.

Seriously, this is what you are going for. Sometimes it’s called the “inevitable surprise.” I think Aristotle’s phrase was “inevitable and unexpected” but I suppose that depends on who is translating.

So we’ll start with Rule #2 and a quick tutorial on plotting

Plot

Plot is “a system of compulsions to the end … leading to the final breakthrough, when meaning is revealed and emotion felt.” – Oakley Hall, from The Art and Craft of Novel Writing

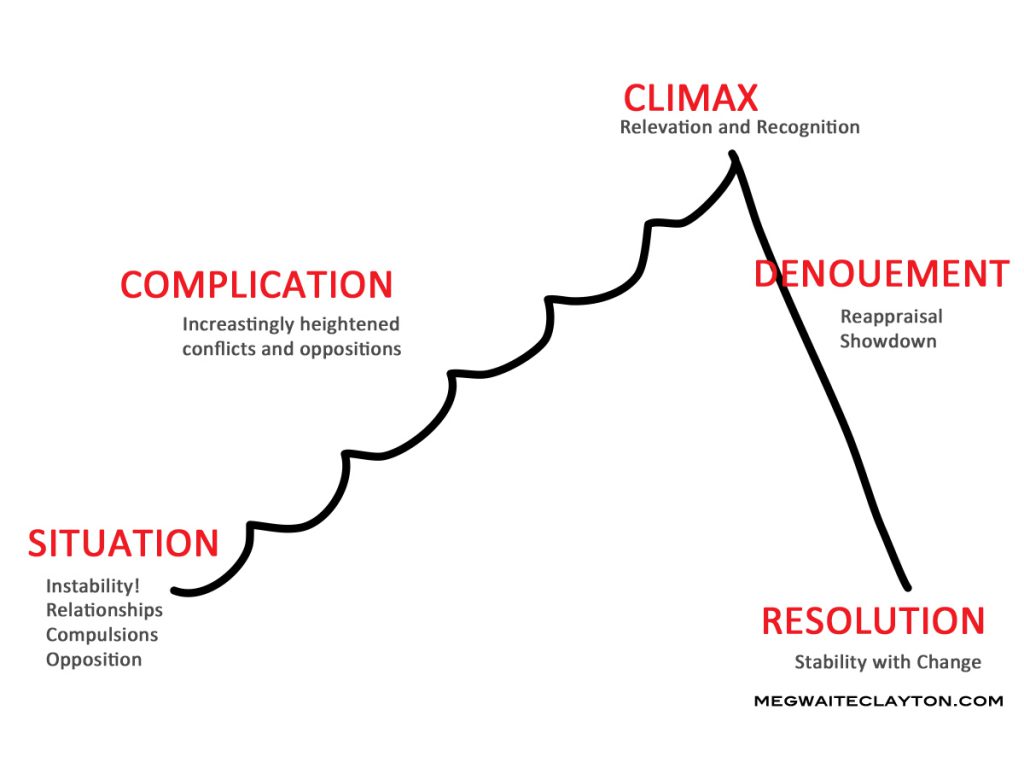

FREITAG PYRAMID is the classical structure: 3-acts built on two reversals (can be 5, or more)

Rule of thumb on Beginnings

Start as Close to the End as you possibly can, and in a moment of instability. Aristotle says begin “in the middle of things.” A good place to start is often at the moment an unsustainable situation receives the last straw. If you need moments from lives before that, you can backfill after the story is going. But don’t start too close to the end or it will look gimmicky.

Compulsions

Start with a character who wants something, is compelled toward something. The reader is basically going to borrow his compulsion to read from the characters compulsion to … whatever he’s compelled to do.

The Two-Shoe Drop

- Everything that happens in the ending has to be set up before hand. The reader has to hear the first shoe drop somewhere for the second shoe to have power.

- Otherwise, an ending seems arbitrary.So for example, if you are going to destroy Los Angeles in an earthquake at the end, or your hero is going to heroically save say, an adorable puppy from a house brought down by a quake, you need to have a tremor sometime earlier in the story.

- Your ending shoe drop should be the most important one.You can have more than one, but you have to have the most important shoe drop very near London. Otherwise, you have a long, boring last paddle the reader has to slog through. And if it’s really funny, maybe that’s ok, because funny covers a lot of sins. But even then, put the funny before.

Ways you keep the compulsion going (and the reader) include

- Obstacles to be Climbed Over, Tunneled Under, Pushed Aside or Blown Up — Strong forces within and outside the character which push him toward one course of action meet strong forces within and outside that push him the other way

- FWTBT bridge or Javert to Jean Valjean in Les Miserables — Note that right against right makes the most powerful opposition

- Faulkner: the best fiction comes from the heart in conflict with itself

- ALL TRUE SUSPENSE IS A DRAMATIC REPRESENTATION OF THE ANGUISH OF MORAL CHOICE

- Foreshadowing: the gun on the mantle in Act I; Or more subtly Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms opening “The leaves fell early that fall” presaging an early death

- Promises Made and Kept

- Jane Austen’s Emma: Emma Woodehouse, handsome, clever and rich, with a comfortable home and a happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence: and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her. —> a promise that we are going to see Emma stressed and vexed.

- Schindler’s List (Thomas Keneally): Opening para shows Schindler comfortably dressed heading for his chauffeured limo, followed by “Watch the pavement, Herr Schindler. It’s as icy as a widow’s heart.” — and that is the story in a nutshell.

- Incompletions that are Later Completed — clues, what does that mean? Sherlock Holmes

- Questions that are eventually Answered — e.g. All the Light We Cannot See: what is it with this stone?

- Dangers that go either to Safety or Disaster — Gatsby’s pursuing Daisy

- Maguffin — something precious and potentially dangerous, for the possession of which forces are contending. Like the stone in All the Light.

- Lit Fuse (lack of Time, which is really a type of Obstacle) — the Nazi at the Door

Endings

So the ENDING —

- Main climax leads to either a winding down of action or a triumphant high-pitch closing; either way the conflict is resolved and our initial concern changes to something else (e.g. wanting a secret be kept changes to the consequences of the secret revealed)

- when a story’s ending is properly set up, it falls like an avalanche — your job is to describe the stones as they fall

Fiction is a process of change — which comes with discovery or recognition:

- Epiphany

Your protagonist realizes something they haven’t before - Reappraisal

Your protagonist takes that realization and works through mentally what it means to them (note, this does not necessarily have to be seen by the reader) - Action

Your protagonist ACTS in a way that leads to a transformation. Someone else acting to save your protagonist simply is not compelling - Transformation (or loss of last chance to change)

The Most Important Elements of an Ending, a bit more specifically than Rule #1

- Action by the protagonist. If the ending is brought about by some other force, it is just not as satisfying

- That second shoe HAS to be the most important shoe drop

- The inevitable surprise — what the reader wants but not how they expect it. If you give them what they expect, they might wonder why they didn’t just write it themselves.

- Connectedness

Adding power to endings

- Connectedness

- The Symphony: As much of the symphony you have set in motion to play over the course of the book coming to play together at the end.

- Often our deepest sense of character comes from symbolic association.

- Symbols register in the reader’s subconscious, and contribute to the symphony in the end in wonderful ways.

- Note that you can’t do this all in one draft; it takes rereading and rereading to see what your symbols are, and to nudge them up and together.

- SO REVISION:

- If you think, I’m going to make a symbol here of a thunderstorm, it’s going to represent love — that symbol is probably going to clunk.

- Just write a draft, and then read it and reread it.

- Reread it more.

- And more.

- You are looking for what your own subconscious has done, so you can fine tune it.

- What subtle symbols have you used?

- metaphors?

- connections?

- accidental repetitions?

- See what subtle repetitions you’ve used and see what your symbols and metaphors are, and nudge them to better use.

- The Symphony: As much of the symphony you have set in motion to play over the course of the book coming to play together at the end.

- Echo scenes: A scene at the beginning is echoed, but changed

-

- e.g. FWTBT Robert Jordan lying on the pine needles.

-

- Tragedy and Hope. Or, if you can do the reverse triple flip: Tragedy, Hope, and Laughter. If you can make people laugh and cry at the same time, you will be famous.

Meg Waite Clayton is a New York Times bestselling author of seven novels, most recently the National Jewish Book Award finalist and international bestseller The Last Train to London. Her prior novels include Beautiful Exiles. Her prior novels include the Langum-Prize honored The Race for Paris; The Language of Light, a finalist for the Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction (now the PEN/Bellwether); and The Wednesday Sisters, one of Entertainment Weekly’s 25 Essential Best Friend Novels of all time. She has also written for the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Washington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle, Forbes, and public radio, often on the subject of the particular challenges women face.